CAI

Cai Leman’s father used to say the men of Trintan were not ones for expressing their feelings. According to him, feelings were for women, children, and more emotional animals, like cows. After five centuries of Pentan rule, the men of Trintan had learnt that life was hard and that is how it would always be. They carried on with their duties toiling in the fields and tending to their crops and livestock with dignity, whether the sun blazed, or the rains came. That was the Trintan way. Was his father right about this? Cai wasn’t sure, but thinking about it, a lot of the man’s ideas were unconventional. No one else claimed that chickens were not to be trusted, or that clouds were government spies. He once accused his wife of committing adultery with a ghost. And when Cai was married, his father’s wedding gift was words of advice about animal husbandry, which did not impress his bride.

Whether Cai Senior did speak any truth ultimately was a moot point since he was long gone. It was up to Cai whether he expressed his feelings, and at that moment as he stood at the river’s edge in the south field of his farm, his feelings were ample and crying out for attention.

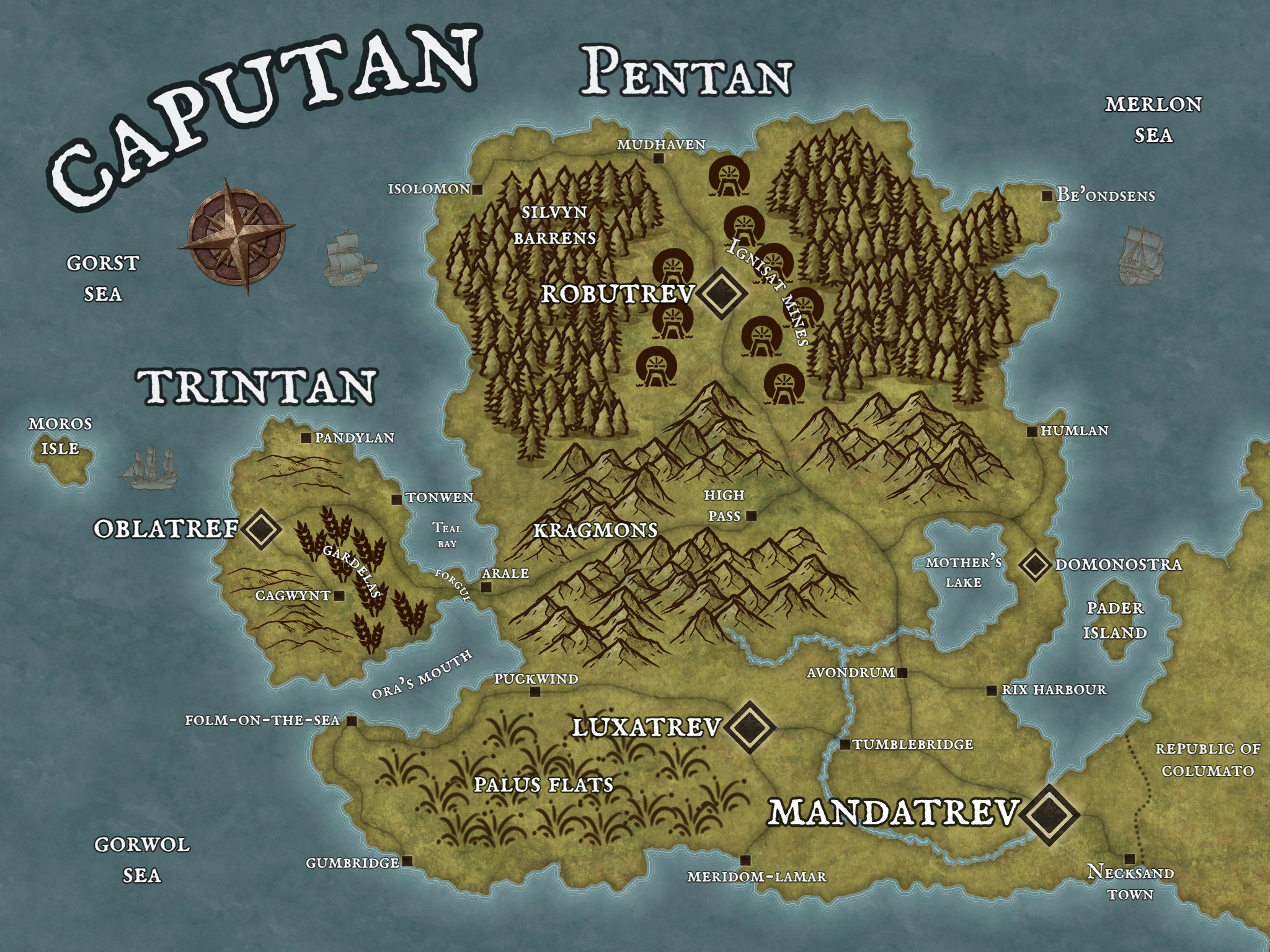

Earlier that morning, he’d noticed one of his ten prized grindor sheep was missing. Grindor wool was reputed to be the most resilient fibre in the human realm, and one season’s worth of wool from his animals represented a year of income for Cai. But their purchase had left him with considerable debt, and he couldn’t afford to lose a single animal. Panic set in as he searched the whole of the forty acres of farmland he’d inherited from Cai Senior after his passing. There was no sign of the ruddy creature. That is, until he checked the river. There, pressed up against deadfall was its soaked, bloated body. When Cai saw it, he dropped to his knees and felt a throbbing in his stomach. He remained in the same position for what felt like hours, but what was likely no more than seconds. Unsure of what to do, his mind took him to thinking about his father. He stared up at the blue skies, watching the billowing white clouds – which painfully looked like wool – drifting away across the green-striped lanes of the Gardelan plantations from his home on the outskirts of the town of Cagwynt.

As memories and thoughts violently clashed inside Cai’s head, he felt his heart beating faster and faster like a madding drummer was in charge. He tried to take deep breaths and buttoned up his shirt. Nothing felt right – his chest was tightening, his hands were dripping with sweat, and black stars flickered across his vision.

“Get home,” he said aloud, and he got to his feet and strode across the south field towards his house.

Cai bashed the door against the wall of the farmhouse as he slammed it open, ignored his wife Ilsie who was sitting by the fire stirring cawp in the pot, and strode into the backroom where he fell onto the bed – face first – like a desperately thirsty steed reaching a trough.

“Sacred Mother wept, Cai. What’s wrong with you?” Ilsie said from the doorway, but he could not see her. All he saw was darkness. Against his face, he felt the knitted grindor wool quilt that lay on their bed. The huge, impenetrable sheath was folded in two and covered the whole of the bed when draped over it. As he struggled to breathe, doom filled his senses like the human realm was ending.

“Cai, what is it? What’s wrong with you? Are you sick” Cai felt Ilsie’s hand on his back.

“Dearest Family, you’re trembling like a leaf,” she said. “What happened to you?”

“Leave me alone,” he said with a muffled voice. “You can’t help me.”

“What? I can’t hear you, Cai.”

“I said, leave me be. I am beyond hope.”

“Get your face out of the quilt, man. I don’t know what you’re saying.” Ilsie’s mouth was right next to his ear. But he didn’t want to face her. He didn’t want her to see him this way. She could not help him; no one could help him. Inside, he felt that the dam holding back his feelings was starting to break apart and a huge wave of sadness pushed up through the back of his neck into his head, and he started to sob.

“You better not be soaking that quilt in tears and snot. Two years it took Mother to make it. And she won’t be making us another one from beyond the grave.”

That was enough. He turned around onto his back, red eyes full of salty tears and nose dripping.

“Hock your quilt. Can’t you see I’m dying?”

“Hock my quilt? You better be dying if you’re going to speak to me like that.” Ilsie stood in front of him with her hands on her hips. She had a wrinkled brow, and he could see her nostrils flare. He knew he was in trouble if the nostrils flared.

He wiped his nose with his sleeve and rubbed his eyes. “It’s ugly and thick. Why the hock would we need such a thing anyway? It’s big enough to cover the house.”

“Cai Moblin Leman. How dare you. That was our wedding present.”

“It wasn’t our only wedding present,” Cai said, sitting up and exhaling through his pursed lips.

“Oh yes, the advice your father gave you about breeding goats. Guidance on getting a billy to mount a nanny has so much more value than some collection of pots or a silly blanket.”

“He gave us the farm as well.” The wave of panic seemed to be passing, and Cai’s breathing was easing.

“Someone had to take the farm. Your brother sure as eggs didn’t want it.”

“My brother didn’t…” Cai was uncertain of how to finish his sentence.

Ilsie reached over and stroked his hair. “What is going on in that head of yours?”

Cai shrugged; he wasn’t sure where to start. “Feelings…”

“Feelings?” she repeated. “What do you mean by feelings?”

“I – er – don’t know.” He bit his lip and dropped his head into his hands.

“Suit yourself then. I need to get back to the pot.” Cai heard the backroom door screech as it opened slowly.

“You’ve been so strange lately,” Ilsie said. “Keeping to yourself. Regularly missing domol on faith days. Staring silently out of the window every evening with that pipe in your mouth, and don’t get me started on how much bush you’re smoking. Now this… It’s like you’ve forgotten how to live, or you’ve become scared of living.”

“Just leave it, will you?” Cai said, holding his head tighter in his hands.

There was a moment of silence before her next words. “Is it related to your birthday?”

What?” Cai looked up and felt affronted.

Her eyes narrowed. “You’ll be three and forty in a few weeks, won’t you? Same age your father was when he dropped – er – when he left us.”

Cai felt his own nostrils flaring. “Stop it with your digging, woman,” he said, his voice rising. “It has nothing to do with my birthday. Leave me and get back to your hocking pot, will you?”

Cai closed his eyes and heard the door shut as she left the room. He pondered her words – was he afraid of living? He didn’t think he was, but she was right – life had become stale of late, and beneath the surface, things – feelings – were bubbling away that he didn’t understand. The only remedy he could think of was change, and that change could only mean one thing; something he had tried avoiding for most of his adult life; something his father most certainly wouldn’t have approved of. But for Cai, at that moment, it was the only idea that made sense.

Pingback: INTRODUCING: By the Blood of Brethren and Blackguards - RH Williams