CAI (III)

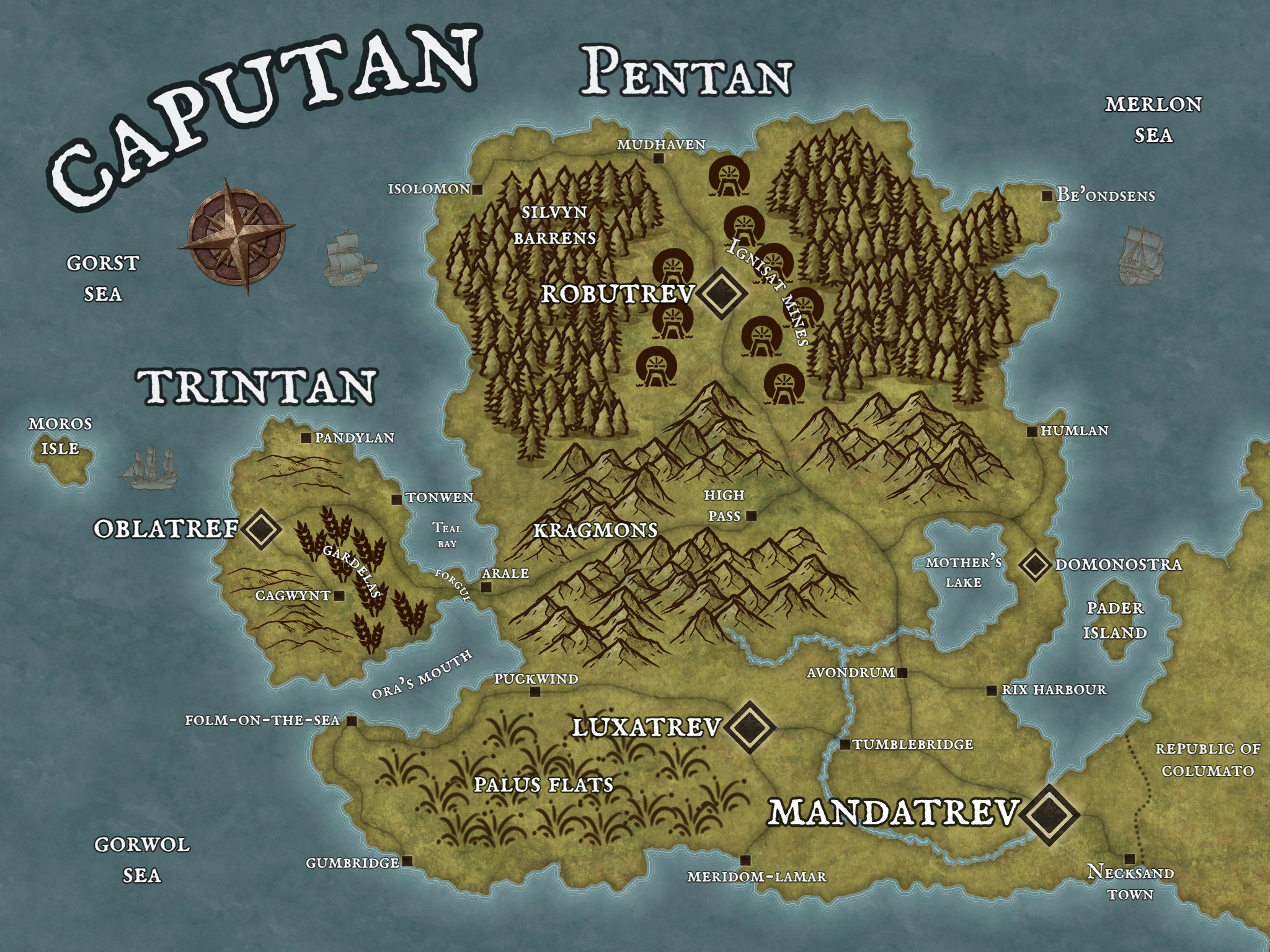

As Cai approached his brother’s farm, he tried to remember the conversation that led to their year-long estrangement. It took place during the previous-to-last Festival of the Hungry Cousin – a time when blood relatives got together and expressed their gratitude to the Sacred Family for all they had by eating too much, drinking too much, and quarrelling too much. Despite their father’s allegiances to the old gods, their mother had instilled in them a fondness for this festive day. As always, Rolo came bearing gifts, which included the Puckwind Turkey that formed the crux of the feast. Cai played host, while Ilsie prepared the meal in the house, and he and Rolo sat outside in the front garden supping ale and putting the world to rights. Being Decembrus, the cold winter air snapped at them both, but their coats and the warm layer from the Pandylan ale made it all the more tolerable.

“Your brown bean crops aren’t looking too good,” Rolo said, pointing his tankard in the direction of the south field.

“Aye,” Cai said; his brother’s comment came as no surprise. “Think it’s mudflies.”

“Oh muckballs,” Rolo said, lowering his tankard slowly. “If you’re right, it’s the end of your brown beans. That happened at old Hektor’s place, and he had to burn his crops.”

“I remember him – but I thought he died ages ago.” Cai turned to face his brother.

“Rolo sighed. “He did, poor hocker poisoned himself with brenlock. After the crop failed, he had nothing left.”

“Poisoned?” Cai said. “With brenlock? Thought they used it in salads.”

Rolo’s brow furrowed. “That’s river brenlock. Pond brenlock is the stuff that kills.”

“He must’ve known his plants.” Cai sipped on his ale.

“Trial and error I believe,” Rolo said. “His wife, Maja, told me she saw him in tears, stuffing himself with leaves. Assumed he was trying to lose weight. But she found a note… afterwards.”

“Oh.” Cai dropped his head until a thought came to him. “I’m sure I’d heard it was his heart.”

“It’s what his family told everyone,” Rolo said. “Hocking Cognati don’t approve of suicides, and they’ve been known to appropriate the possessions of those who die in such ways; claim the inheritance as their own.”

“Rats,” Cai said. “Poor Hektor must have been desperate.”

Rolo took a sip of his ale. “He was. Had nothing left after the brown beans. But he didn’t help himself – the old fart was stubborn. Much like Father, he wasn’t one for progress.”

Cai turned and looked at Rolo. “Because he didn’t take up the bush? That didn’t mean he was stubborn. He and Father were cut from the same cloth. They were principled men. The last of a dying breed here in Trintan.”

Rolo shook his head. “Brother, such men are not dying – they’re dead. Long gone and returned to the dirt.”

“That’s not true,” Cai said. “There are still plenty of us here.”

“Us? Ha. Your place here may be the last farm in the county that hasn’t yet taken up bush.”

“I don’t care. I stand by Father’s beliefs. He was a good man.” Cai filled his mouth with ale and thought best to try and calm the discussion before it spiralled. “I know you and he had your differences…”

“Aye, he was a fool, and I am not,” Rolo scoffed.

Cai bit his lip. Rolo was evidently not interested in calming the discussion.

“He was not a fool,” Cai said, adamantly. “He could see the lay of the land; he knew what bush was doing to our people. He stood his ground until the end…”

“Until he dropped dead at an early age – collapsing out there on a withered crop.” Rolo gestured to the field again. “That’s where his principles took him – to a world of stress and discontent.” Rolo raised his finger in the air and pointed at his brother. “And you know something, if you’re not careful, you’re next. If that is mudfly then this crop is a goner. Then what will you do? Have you got insurance?”

Cai didn’t answer the latter question. “I certainly won’t be selling my arse to the Rix and the ruddy Familists – that’s for sure.”

“Dear Cai, you’re so like him. So hocking naïve about the way of things in the human realm.”

Cai felt his hackles rising. “Father was not naïve – he was principled!”

Rolo scoffed. “A principled man that was fearful of chickens and suspicious of clouds. A principled man who slept in the barn for a month because he thought our mother was cheating on him with a malevolent spirit. Face it, Cai, Father was a paranoid lunatic.”

Cai stood up and put the tankard down on the wall. “How dare you come here and besmirch the name of a great man in the house he lived in all his life?”

“Lived in and died in. Brother, I don’t mean to insult you. But don’t you see? You’re doing the same as he did – denying yourself and Ilsie a decent life by not growing bush. And to what end, eh? To deny the bastard blackguards of Pentan an insignificant additional amount of coin each year? Think you’re sticking it to the Rix, do you? I guarantee you; he has no idea who you are or what your troubles may be, and your denial of the bush crop makes no difference at all to his daily existence.”

Cai crossed his arms and grunted. “That’s all fine and good from a man without principles. As soon as you could, you left this farm to go off on your own to find your way.”

“And I was shunned by Father and left out of the inheritance for it.” Rolo huffed. “And what do you mean by my way – the fact I’ve made a success of myself farming bush or is it because I prefer the company of men to women?”

“You know Father wouldn’t have approved…”

“I don’t give a rat’s arse what Father would have approved of. He was a sad, angry little man who couldn’t take responsibility for his life and his family – and you know something? You’re just like him.”

Cai put his hands on his hips. “Alright, that’s enough – get out of here. I won’t have you talking like that about Father or me. Get out of here. Get your gifts and go. Today is about family and I don’t want you here with us. Go back to your fancy bush farm and spend the day with your boyfriends.”

Rolo did not enter the house to retrieve his gifts; he downed the ale, threw the tankard in the direction of the vegetable patch, and stormed off.

#

Cai stood at the end of the Rolo’s farm lane and pursed his lips and blew. He didn’t regret the words he spoke that day as much as the silence that followed for the months afterwards. Reality had – perhaps finally – hit home, and it was time to face the truth. Rolo always saw through Cai Senior’s strange behaviours and thought processes. From an early age, he saw the growing number of bush farms in the Gardelas and pushed his father to switch crops. There was a huge market for it in Pentan and growing the plant provided farmers a solid, healthy stream of cash; certainly, far more than the other crops or outputs could. Their father pushed back repeatedly, saying he would not support the filthy economy. Cai sided with his father, but Rolo grew disillusioned and eventually left at the age of sixteen to work on another farm, and before long, using a combination of savings and a loan he was able to set himself up. When their father died, Cai inherited the farm but even in the early days that followed, it was clear Cai’s loyalty to his father and the old ways would not provide a smooth path. Now, here he was, twenty years later finally deciding to switch sides. His father would be turning in his grave but that was not Cai’s concern – not any more anyway. If he didn’t change something, he would certainly be there with him. Better to remain alive and risk the wrath of the dead than to join them in the dirt as a faithful servant.

Cai ambled up the lane towards Rolo’s house and stopped. It looked bigger than he remembered – had his brother extended it in recent months? It was now twice as big as his own. In fact, his and Ilsie’s house could no doubt fit wholly in the front chamber of Rolo’s abode. The front door opened, and a young man rushed out carrying some items in a box. He was followed by a gentleman dressed in a shirt and breeches and who had a pipe in his mouth; it was his brother, Rolo.

“Don’t forget – we need that back by next Marday,” Rolo yelled. “I’ll be heading to the market.”

He stopped at the open door and his mouth fell open when he saw Cai. “Well hock me sideways, if it isn’t the, what are you now, a sheep farmer?”

Cai dropped his head and plodded nearer.

“Is it a good time?” Cai asked in a deep, sullen voice.

Rolo shrugged and blew smoke from his mouth and Cai took that as a yes. He approached and stopped by the small gate in front of his brother’s house. Rolo remained by the door at the other end of the path.

“I need you to not say anything for one minute,” Cai said. He looked up briefly, saw Rolo nodding, and then continued to stare at the path. He felt vulnerable and exposed but he was desperate, and he took a deep breath.

“I’ve been having these thoughts. Dark thoughts. About the end of things. About the end of me. And about it happening like it did for Father. I know now Father was wrong, wrong about a lot of things. And – and – I’m not ready to follow in his footsteps. I’m not ready, I tell you. I want to change things. You were right and I need to change things. I need your help. Will you help me, brother?”

Rolo cleared his throat. “You better come in.”