ONA (II)

Ona’s classroom was only half filled; attendance had been poor of late as children spent less of their time at the schoolhouse and more time at the domol, or in the case of Pimmy, the market selling bread. Regardless of the attrition, Ona carried on with her teaching as best she could. She’d split her lessons for the day in two – the morning session would cover her favourite subject, natural sciences, and the afternoon would be dedicated to arithmetic and reading. As they neared the luncheon break, she stood at the front of the classroom, talking to the children about animals.

“Can anyone here tell me the word we use to describe all creatures that share common characteristics and breed together?” Ona said. “Cats, for example. What are all cats?”

“Devious hocking turds,” said a girl’s voice from near the back.

Ona’s jaw dropped. “Jeeny, was that you?”

“Aye, Miss,” Jeeny’s head popped out from behind Bonta’s big frame. “It’s what Nana calls them. She’s not a fan.”

“I gathered. But firstly, we’ve spoken before about using language like that in the classroom. Secondly, that’s not exactly what I meant. See, there is a word that describes what all cats are, as well as all dogs, and all harp eagles and Columato wolves. Each of these animals shares the same characteristics and can only breed with other members of the same group.”

“Miss, what does breed mean?” asked Bonta, a big innocent boy who, despite being the height of a full-grown man, still sounded – and perhaps thought – like a five-year-old.

“It’s what your Ma does for coin in the docks,” yelled Matoon, a cocky bush farmer’s son, from the other side of the room.

“Matoon, enough of that,” Ona said, and she shook her head. “Bonta, breeding is when male and female animals mix their seeds to make baby animals… More or less.” This was not the time to get into that discussion, Ona thought.

Bonta appeared deep in thought for a moment. Ona knew another question was coming, but she hoped for his sake it would be a sensible one, otherwise Matoon would be all over him.

“So different creatures can’t breed together?” he said. “I can’t breed with a wolf?”

Ona’s hand went to her mouth.

“Bonta wants to hock a ruddy wolf.” Matoon guffawed and hit the desk with his hand.

“Matoon!” Ona said. “Don’t be so cheeky. No, Bonta, you can’t breed with a wolf.” Whether or not it was a good idea to ask, she couldn’t help her curiosity. “But – erm – why would you want to breed with a wolf anyway?”

“I love wolves, but I can never be a wolf, so if there’s a chance my children could be wolves or maybe even just a bit wolf, I would like that.”

“Right…” Unsure of what to say, Ona thought it best to get back to the proper discussion. “We’re getting off track. The word I was after was cista. Only creatures of the same cista can breed together to make a baby creature. Similarly, all creatures in a cista share the same features or characteristics. They look the same.”

“So different animals are in different cistas?” Jeeny asked.

“Yes they are,” Ona said.

“And how many cistas are there?” Jeeny said.

“There are millions of cistas of animals, Jeeny, but we don’t yet know how many exactly. There are also millions of plant and fungal cistas as well.”

Near the front, Sarus, a dark-haired and thoughtful girl who’d been quiet for a while, spoke up. “Miss, how did the Sacred Mother birth all these millions and millions of different living things?”

Ona took a deep breath, knowing this was a topic she had to handle very carefully. “What did they tell you at the domol?”

“They told us the Sacred Mother was an incredible being with all the power in existence, and when she birthed the human realm, she performed the greatest miracle ever. But it’s a lot to believe.”

Ona bit her lip. “Right. And she did this twelve thousand years ago?”

The little girl’s response was a mixture of a nod and a shrug. All of a sudden, Ona felt like she was standing in the middle of a storm, trying to withstand powerful winds that wanted to carry her away. She wrapped her arms around her body and held tight. Inside, she had a dialogue going on: Go on, part of her said. Tell the girl it’s all bullmuck; that the Cognati are charlatans and con artists; that the Sacred Family aren’t real, and even if they are, there’s no way in the human realm one female deity could have birthed absolutely everything; and, by the way, all that exists right now was definitely a lot older than twelve thousand years old. In fact, the human realm was likely millions upon millions of years old. Maybe even billions of years old. Tell her everything. No, the other part said. The Committee are watching. If it got back to them, she and Master Poones would be charged with sinsanguity and sent to Moros and the schoolhouse would be closed immediately. But she couldn’t leave it like that; she wouldn’t tell them everything, but she would give them a few things to think about; a selection of ideas, perhaps? Surely the Cognati wouldn’t deem a few wild theories to be problematic?

“But you know,” she started, “there are some who think the human realm is a lot older than twelve thousand years, that it may be millions or billions of years old, even.”

“And they think people and animals have been here for that long?” Sarus asked.

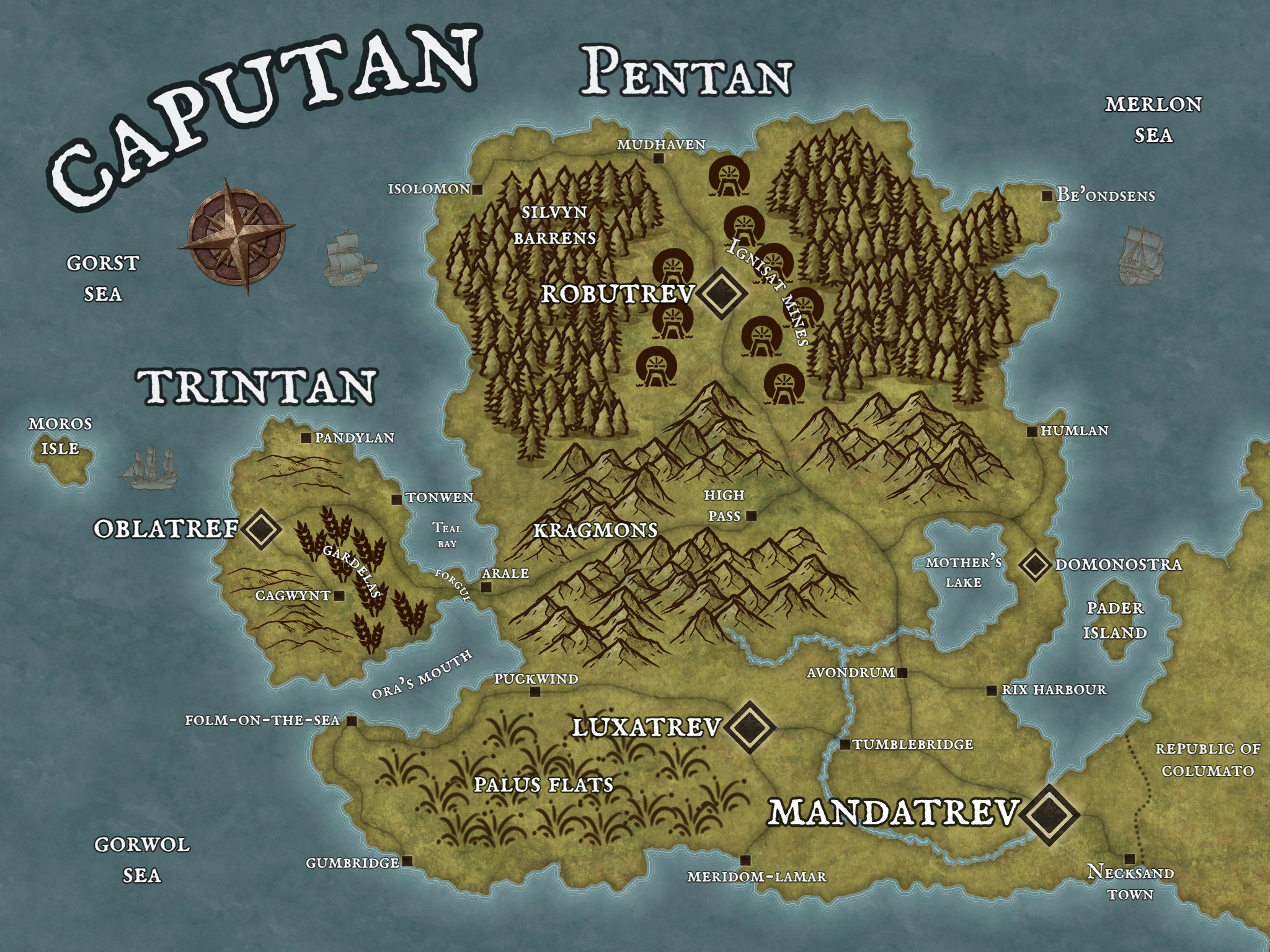

“Not exactly. They also think that when life started it was very simple at first, and that over time it changed, became more complex. It’s a theory called mutamitis that some of the natural scientists in Luxatrev believe in.”

The children were wide eyed, and a few jaws had dropped in the classroom. Was it awe or confusion? Ona couldn’t tell, but she’d started it now and she’d have to finish it. A half-baked truth was more dangerous than a fully cooked lie.

“Living creatures can change into other living creatures?” Jeeny said. “Can we change into animals?”

“So I could turn into a wolf?” Bonta asked, hopefully.

“I want to be an eagle,” Jeeny said. “One of those big ones that catch rabbits.”

Ona sighed. “No, it doesn’t work like that. If it’s true, the change would be gradual – very slow – and it would take millions of years for any change to be significant.” She saw puzzled faces and thought about how best to explain it to them.

“Right,” she said. “Imagine two deer in the forest and one is much faster than the other. If a wolf came and attacked them both….” Bonta sat forward on his seat and furrowed his brow.

“…the faster deer has a better chance of running away and surviving. As that one lives on, it can have babies that are also faster. Over time, more and more fast deer will be born. The slower deer on the other hand will continue to be hunted down and won’t be able to have as many babies. Eventually, all the deer in the forest will become fast deer. Nature will have picked those kinds to be the main type of deer, and the whole cista will be fast deer.”

“Poor wolf will be hungry,” Bonta said.

“Does that mean animals that lived a million years ago would be different to those that live now?” Sarus asked.

“Probably. It’s certainly what morastones tell us,” Ona said.

“What are morastones, Miss?” Jeeny asked.

Ona turned around and started drawing on the blackboard. “They’re rocks with remains of animals or plants trapped inside them. When the thing died, its body dropped to the bottom of a river or the sea, and over time, layers of sand and mud pilling up on top would have squashed the sediment, turning it into rock. And the remains of the creature also became part of the rock.”

“Where are these morastones, Miss? I’ve never seen one.” Sarus said.

“Not many have been discovered. Those that do are difficult to preserve. The rock is very fragile and and extremely heavy. So moving them to a museum is difficult. Those that have been recovered are kept by natural scientists in Luxatrev. The same people who came up with the idea of mutamitis.”

Matoon sat back in his chair and crossed his arms. “Before he says anything, let me speak for Bonta and say I’m very confused. I don’t understand how this all fits with what the Cognatus told us about the human realm and the Sacred Mother.”

Ona bit her lip. Had she said too much? There was nothing she could do about it now, other than try and minimise the damage. “No, it doesn’t, and I guess it’s just another way of thinking about the human realm and how all the creatures here exist and have come into being.”

“We should ask the Cognatus about it when we’re at the domol tomorrow,” Jeeny said looking over at Matoon. “He’ll explain it to us.”

Ona pinched the skin on her throat. “No, I wouldn’t do that, children. I suggest we keep this type of discussion between us and avoid mention of mutamitis or morastones with the Cognatus. He won’t want to talk about that and will probably just get angry with you.”

Just as she finished her words, the school bell rang to tell everyone it was time for luncheon break. The kids leapt from their desks and the conversation ended abruptly. She had – it seemed – been saved by the bell, for now at least.